A new study from Costa Rica uses sound to track biodiversity returning at scale.

Scientists use soundscape data from 119 sites across Costa Rica to reveal patterns of ecosystem recovery.

PorGiacomo Delgado

·

4 de febrero de 2026

·

6 minleer

He lets up on the gas of the roaring ATV, bringing us to a stop. The older man points to a towering tree growing alongside the muddied path, “Míralo”. Look at him. His tico accent stresses the “R” in the word. “¿Qué tipo de árbol es?” I ask. What type of tree is he? The man places his hands familiarly on the giant’s trunk, as if greeting an old friend. He tells me it's a Guanacaste tree (Enterolobium cyclocarpum), one of the larger ones in the expanse of forest that he protects. The tree carries a special significance. It’s Costa Rica’s national tree and the namesake of the country’s Pacific Northwest province that we find ourselves in. The man compares the tree to a work of art. He asks me whether I think this tree is worth more standing and alive, or felled and cut up. The question is mostly rhetorical, I answer anyway: the living tree is priceless. His eyes light up, “Exacto”. Exactly. Unfortunately, the world does not seem to agree. He tells me bluntly: If he cannot afford to provide for himself or his family, he will be left with no choice, the tree will come down.

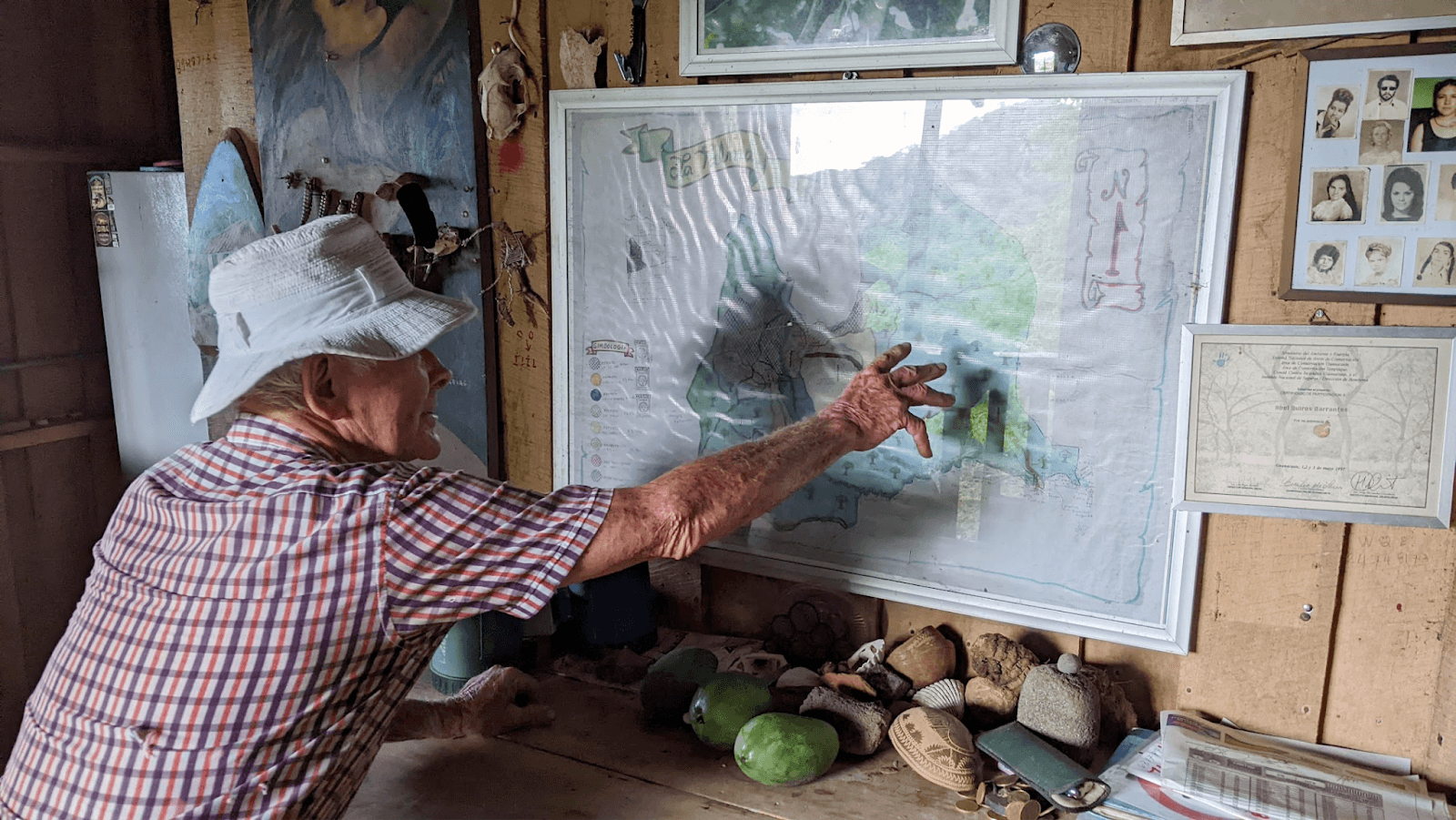

This man (photo above) is one of thousands supported by Costa Rica’s Payment for Ecosystem Service (PES) program. The program - the world’s first national-scale PES - has been directly compensating local landowners for their stewardship of forests for nearly 30 years. I had this particular conversation almost four years ago and it's one of many like it that I had during my time in Costa Rica. I was there as an ecologist, looking to investigate patterns of ecosystem restoration and biodiversity recovery, but it was in these interactions that I found the real meaning of this work.

An indigenous park ranger who travels for days on foot to patrol his community’s forests. A young man who finally accomplished his dream of working for the National Park Service. A woman old enough to be my grandmother, who, after guiding me through her forest, insisted on making me lunch. Everywhere I went, a deep love for nature spilled out from the people who lived alongside it. But there was also an ever-looming economic pressure. The indigenous ranger who walks because he earns so little that he cannot always afford bus fare. The national park employee whose government wages only recently became competitive enough to leave a banana plantation. The kind old woman worries that her family will be forced to sell off the forest after she is gone. These stories highlight what many in the environmental movement know all too well: that people everywhere have an intrinsic connection to the nature that sustains them. When they destroy it, it’s because they have been left with no other choice.

International policy often treats nature restoration as an impossibly complex problem, while quietly reinforcing the same feedback loops that drive environmental loss. Vast public subsidies continue to support activities that degrade ecosystems, increasing inequality and economic pressure on the very communities that depend on nature. This pressure, in turn, accelerates further destruction, reinforcing a cycle of loss. This same wealth is then used by the rich to fund ever more destruction. Costa Rica chose to interrupt this loop. It directly confronted ecologically damaging behaviour; banning forest conversion and taxing gasoline use. Using the money collected, it then began to redistribute wealth directly to local landowners with forests on their land through the PES. The result? A new feedback loop. While Costa Rica used to have one of the world’s highest deforestation rates, today more than half the country is covered in forest. The PES helped forests to regrow on abandoned land and carbon storage increased. It is perhaps the greatest forest restoration success story. But until recently, it was only that - a forest restoration success.

Our research team, made up of scientists from across the world and the civil servants who help administer the PES program in Costa Rica, set out to understand whether the PES has done more than just bring back trees. So we set out to look for evidence of biodiversity recovery. Or rather, we listened for it. Because while I could hear the love of nature in the conversations I had with people, I could also hear the response in the forest. It was in the howling of the monkeys and the chittering of the insects. We decided to use the sounds, or soundscapes, of these forests to evaluate changes in biodiversity. We recorded soundscapes in hundreds of sites across the Nicoya Peninsula of Costa Rica, across a variety of ecosystems. From degraded pastures to naturally regenerating PES forests and protected areas. Using thousands of hours of sound (over two years if they were all played back-to-back) we were able to identify the acoustic signatures of healthy ecosystems and then evaluate exactly how far restored forests in the PES had come since having been cleared for pasture decades ago.

The results, published today in Global Change Biology, provide strong evidence; the soundscapes of naturally regenerating forests in the PES are significantly more similar to healthy mature forests than they are to degraded pastures. These similarities are most pronounced in the frequencies associated with the calls of native animals like birds and insects, suggesting biodiversity recovery. At times, for example, at dusk, naturally regenerated PES forests are virtually indistinguishable from protected areas. Other PES forests - those planted as monoculture tree farms - lack some of the acoustic patterns of protected forests, reiterating previous findings that plant and structural diversity help support wildlife diversity.

Photo: Giacomo Delgado, lead author of the study, is setting up an acoustic recorder in the forest.

These findings represent perhaps some of our best evidence to date that ecosystem restoration can benefit biodiversity at large spatial scales. Until now, we had only local case studies showing biodiversity recovery, but these data suggest that, given the chance, nature’s entire symphony can return. Beyond a simple proof of concept, this is a powerful kernel of hope for a global movement with the shared goal of healing our home. Perhaps even more profoundly, the political context in which this recovery occurred reminds us that nothing happens in isolation. In order to combat our ecological crisis, we must confront the crisis of inequality. Empowering local people and sharing nature’s bounty among all, instead of locking it away for the privileged few, is a radically effective ecological solution.

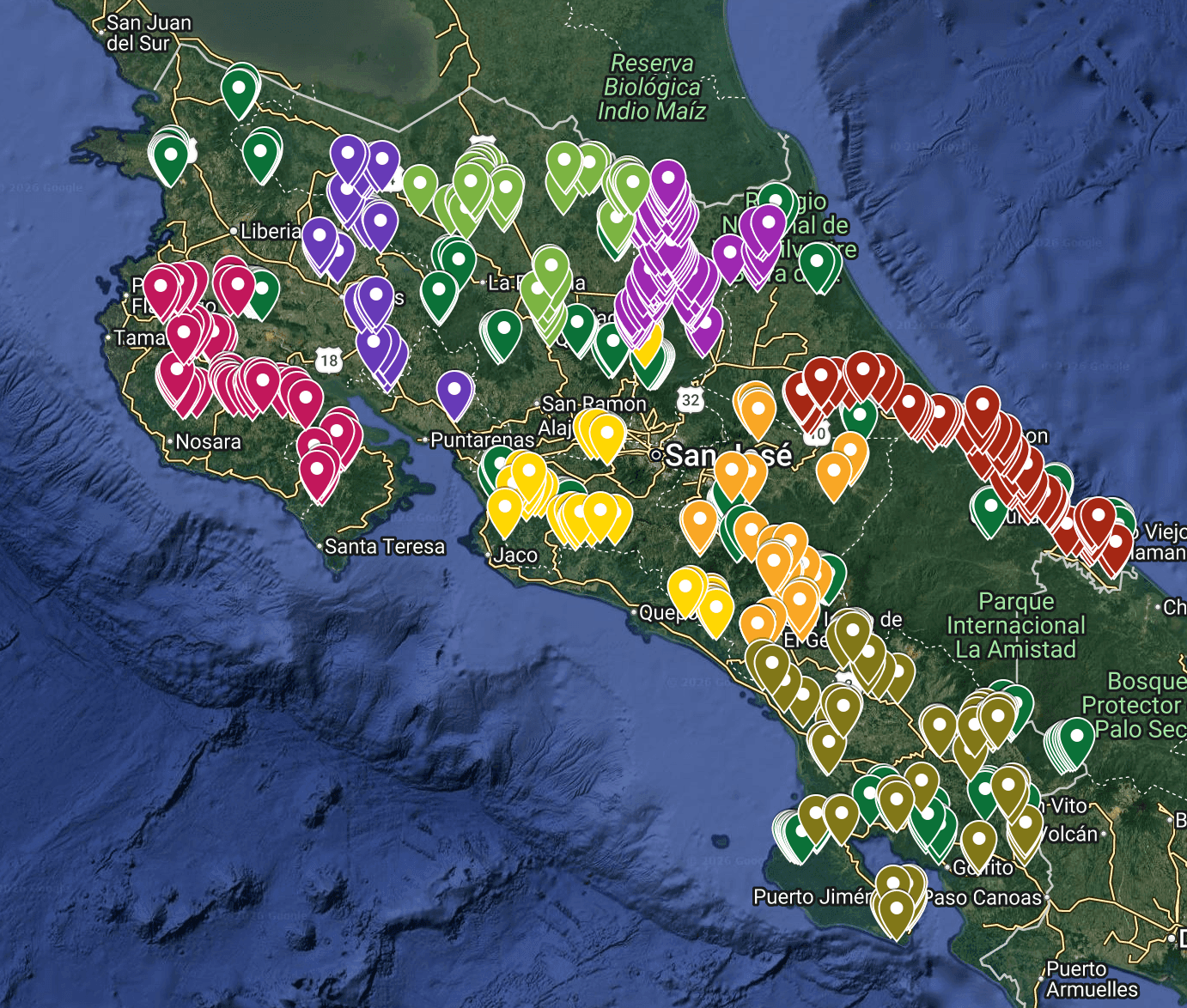

Image: Map showing all sites in Costa Rica monitored as part of the larger study.

Costa Rica is not perfect. The payments offered through the PES (~70USD/ha) are modest and even so, demand for the PES program outstrips the budget by almost 10:1. But the core of the message is plain to see, now backed by scientific data and consensus. It’s also the strategy that sits at the heart of a platform like Restor. Not only does Restor bring together the global restoration movement, but it also aims to put power back into their hands by democratizing scientific insight or using transparency to hold all to account. All PES sites included in this study, along with 2,498 other restoration sites, are publicly visible on Restor through its partnership with Costa Rica’s National Forestry Financing Fund (FONAFIFO). I am hopeful that this research is another note added to the chorus of grassroots movements and global initiatives that grow stronger by the day.

Read the new study published in Global Change Biology.